In the warm, dimly lit kitchens of home bakers and the massive industrial facilities supplying global markets, a silent MVP works its magic. This microscopic powerhouse, a single-celled fungus known as yeast, is the undisputed champion of the baking world. Its story is one of biological elegance, a quiet fermentation process that humans have harnessed for millennia to transform simple mixtures of flour and water into the airy, complex, and utterly irresistible staples we call bread.

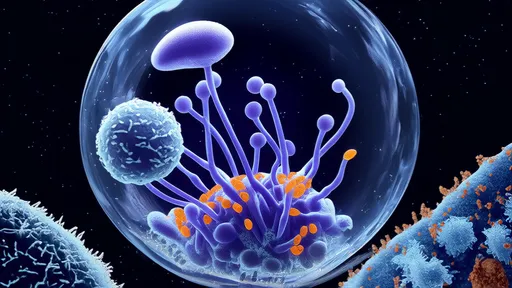

To understand why yeast is so indispensable, we must first look at its fundamental nature. Yeast, primarily the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is a living organism. It consumes sugars and, through the metabolic process of fermentation, produces two primary byproducts: carbon dioxide gas and ethanol. This simple biological fact is the entire engine of baking. The carbon dioxide gas becomes trapped within the stretchy protein network of gluten in the dough, causing it to inflate like a multitude of tiny balloons. This is what bakers call "proofing" or "rising," and it is the sole reason bread has a soft, spongy crumb instead of being a dense, hard tack. The ethanol and other minor organic compounds produced during this process mostly evaporate during baking, but not before contributing to the developing flavor profile of the loaf.

The relationship between humans and yeast is ancient, predating recorded history. The first leavened breads were almost certainly happy accidents. A simple dough of crushed grain and water, left exposed to the wild, would have been colonized by airborne yeast spores and lactic acid bacteria. This wild fermentation, what we now know as a sourdough starter, creates a stable ecosystem where yeast can thrive. For centuries, this was the only way to leaven bread. Bakers would save a piece of fermented dough from one batch to inoculate the next, a practice that continues in artisan bakeries today, creating breads with deep, tangy, and complex flavors unique to their local microflora.

The real revolution in baking's efficiency and consistency came with the isolation and commercialization of yeast. In the 19th century, scientists and entrepreneurs began cultivating pure strains of S. cerevisiae. This led to the development of compressed yeast, a moist cake of live yeast cells that bakers could easily portion and add directly to their dough. Later, technology enabled the creation of active dry yeast, granules of yeast that were dehydrated, giving them a dramatically longer shelf life and making them accessible to home bakers worldwide. The most recent innovation is instant yeast, a finer-grained version that can be mixed directly with dry ingredients, eliminating the need for a separate proofing step in water. This progression has democratized high-quality baking, ensuring reliable results every time.

But yeast's job is far more complex than just producing gas. It is a master flavor developer. During fermentation, yeast generates a cocktail of compounds—including alcohols, esters, and organic acids—that are the precursors to bread's signature taste and aroma. This is often described as the "yeast flavor." The longer a fermentation lasts (as in cold, slow rises in a refrigerator), the more time these flavor compounds have to develop and mature. This slow fermentation is the secret behind the superior taste of artisan and sourdough breads compared to their quickly produced commercial counterparts. The yeast, in essence, acts as a biochemical factory, building the flavor from the inside out.

The baker's control over this microscopic workforce is a delicate dance of temperature, time, and food. Yeast is a living ingredient, and its activity is highly sensitive to its environment. Temperature is the primary throttle. Yeast is largely dormant when cold, becomes increasingly active as things warm up (with an ideal range around 75-95°F or 24-35°C), and will die if it gets too hot. This is why recipes specify warm water for activating dry yeast and why a cold kitchen can slow down a rise. Time is the other critical factor. A quick, warm rise will produce a loaf efficiently, but a long, cool fermentation, often called a "cold retard," allows for much greater flavor development. Finally, the yeast's food source—the sugars present in the flour—directly impacts its activity. Some bakers add a small amount of sugar to a dough to give the yeast an immediately accessible energy boost, ensuring a vigorous start to fermentation.

Beyond the classic loaf, yeast's versatility makes it the MVP across the entire baking landscape. It is the driving force behind a stunning array of products. It creates the ethereal lightness of a croissant and the rich, tender crumb of a brioche. It is responsible for the distinctive holes and chewy texture of a baguette. It even plays a crucial role in sweetened doughs, like those for cinnamon rolls and babka, though its activity must be carefully balanced against the slowing effects of sugar and fat. In every single case, it is the biological process of yeast fermentation that provides the structure and much of the character that defines these beloved foods.

Looking forward, the role of yeast continues to evolve. The growing demand for gluten-free products presents a unique challenge, as these alternative flours lack the gluten network needed to trap CO₂ effectively. Bakers and food scientists are responding by developing novel hydrocolloids and gums to mimic gluten's function, but they still rely entirely on yeast to generate the gas. Furthermore, research into different yeast strains promises even greater control over fermentation, potentially leading to breads with enhanced nutritional profiles, more complex flavors, or faster production times without sacrificing quality.

From its humble beginnings as a wild spore to its current status as a precisely engineered baking ingredient, yeast's journey mirrors our own culinary evolution. It is a testament to humanity's ability to partner with nature's smallest workers to create something greater than the sum of its parts. The next time you tear into a piece of crusty bread or bite into a soft, sweet roll, take a moment to appreciate the invisible, single-celled MVP that made it all possible. It is a timeless collaboration between baker and microbe, a fundamental process that turns the simplest ingredients into one of life's most fundamental comforts.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025